Changing values and selling our work

The fourth UX Scotland took place on the 8-10 June. For the first time the conference was three rather than two days, with workshops now integrated into the conference. Topics ranged from online shopping cart UX to Raspberry Pi music shufflers.

Values create change (but change is loss)

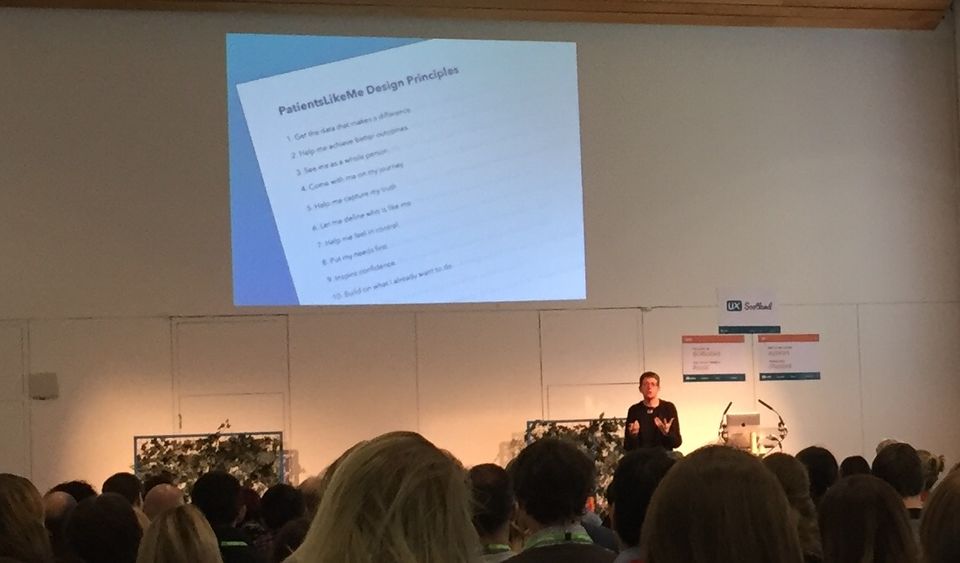

UX veteran Kim Goodwin kicked off the conference. Goodwin is the VP of UX and product development at medical startup PatientsLikeMe. She spoke on how values steer organisations – but that these values are often implicit rather than explicit. At best, an organisation may not be as focused as they could be. At worst, some values may be at odds with each other. PatientsLikeMe had encountered this tension. The company gives people with illnesses a supportive community, and scientists data for research This led to the tension. Scientists wanted as much medical data as possible. However, patients could feel mined or even not be able to answer some questions – what if they couldn’t remember how they felt yesterday?

Identifying a problem is one thing, implementing change is another. Goodwin suggests using the competing values framework to understand your organisation’s values. The four types are adhocracy, clan, market led, and hierarchy. (PatientsLikeMe was something of a hierarchy if only because of the medical considerations). Similarly, change requires different types of people to help it thrive. She also recommended using the continuous change model when you want to create change. It identifies four types of person needed to make change: an autocrat, evangelist, architect, and educator. She’s also found value maps help to make information graspable.

Above all, she suggested a key aspect of human nature to be mindful of is that change is loss. People are adverse to change as in our lizard brain it feels like a danger and a loss. Actually getting change to happen requires acknowledging this and creating a better narrative to give people the ballast to move to something new.

Create a common language

In Goodwin’s talk, PatientsLikeMe managed to foster shared values through resources including design patterns (the medical community is adopting their informed consent guide) and internal promotional materials. (Other organisations doing similar things include the 18F style guide or the Government Digital Service (GDS) ‘It’s OK’ posters). Other speakers echoed this tactic.

Fiz Yazdi and Jesmond Allen spoke on how to help clients start to bring their UX in-house. They suggested embedding culture through resources such as playbooks that the team can use and add to.

Richard Ingram spoke about literally creating a common language across disciplines. He promoted pair writing as a way for content designers to work with ‘subject matter experts’ (though he suggests ‘calling them content leads’). He’s found it both more efficient and more collaborative, “we can’t remember who wrote what line so we have shared ownership”.

And – in one of my favourite talks of the conference – Cornelius Rachieru explained how business analysts aren’t that different from UXers after all. I didn’t know that the Business Analysis Body of Knowledge (BoK) inspired the UXPA Usability Body of Knowledge. And the business model canvas complements the experience canvas. Beyond this, they have a common skills stack that encourage working together.

Service design meets internet of things

Several talks explored service design through lens of the internet of things. This suggests that when it comes to technology the line between service design and user experience design is starting to blur.

In particular, two talks investigated this space – Nick van der Lind’s talk about context, and Stuart Tayler’s about personal projects on raspberry Pi.

Van der Lind’s talk on context explored what makes iOT work. Key examples included allowing for user overrides, and the concept of taking a key idea and then enhancing it. (It also reminded me of Claire Rowlands’s NUX4 talk on iOT).

Tayler’s talk had a refreshingly different format – he ‘showed the thing’ upfront and then contextualised it. He began with a very personal project: making a Spotify music player that he could send music to for his wife and toddler. Through this, he explored what the internet of things is really about (iterating, doing things in software where possible since hardware is hard), and above all, that it’s about creating a service with added value. I’d love to see more talks that skip the preamble and get straight to the thing first.

Both Van der Lind and day 2 keynote Vitaly Friedman mused that the future may be bots. Chatbots, particularly on Facebook Messenger, can already do basic transactions.

Agile is still on the up

Last year’s conference included many talks about Agile, and this trend continued. Anthony Viviano investigated agile in large organisations. He found that this comes down to staggered sprints and an actual discovery. Spencer Turner found that getting an organisation to use lean involves getting involved at the right point of time. Andy Irvine looked at the ‘jobs to be done’ model and how to use it. He suggests some epic stories, job measures, and using personas as part of the jobs rather than getting rid of them completely.

Day 3 keynote Rolf Molich also noted that that ‘you only need to test for 5 users’ mantra isn’t strictly true. However, what it is perfect for is an iteration. So, the GDS mantra of ‘test with 5 users per sprint’ is correct when it comes to agile UX.

We need to sell our results

As someone who’s worked in an agency setting for many years, I’ve been well aware of the need to sell results, and may speakers gave tips to this point.

Molich looked at his learnings from 30 years as a usability practitioner. He noted how UXers need to design their findings to make sure that they’re implemented. This includes making them digestible and adding some positive findings to not only give some reassurance but also stop people changing good features.

Similarly, Paul-Jervis Heath’s talk on using ethnographic research included tips about findings. He chided some UXers for giving observations rather than bringing their point of view to create insights. He also suggested that all good findings are intuitive, not obvious, generative and sticky, and that a good research deliverable has a point of view, considers the audience, and is designed for impact.

Be reflective practitioners

The final point from the conference was that of being mindful of our own work. Many speakers suggested extending the empathy we use in usability tests to our colleagues (though I’d love to see the energy required to maintain this).

More interestingly, several speakers cited the Dunning-Kruger model for bias. It suggests that novices and experts over-estimate their knowledge, while those in the middle do the opposite. It’s a useful model to consider, particularly as all too many bootcamp UXers go into industry assuming they know everything.

Molich led the CUET studies that tested if heuristic evaluations were useful. (Heuristic evaluations are often mixed up with expert reviews. However, a heuristic evaluation is a collection of expert reviews done by multiple people with the same protool.).He’s consistently found different people report different things. This bias is one that’s hard to ignore and should make us pause.

Detailed notes from each session are available as collaborative documents.

Member discussion